Cyan

The enlightenment of an iconoclast

“Finding out about the New York Times bestseller list broke me,” says Cyan Banister.

She’s sitting at her dining room table—a solid slab of wood peeking out from under an eclectic collection including but very much not limited to six sets of takeout chopsticks, a Blitz Spray Horse Plush, and a keto brownie. Record-setting San Francisco rain pounds the windows.

“I wasn’t the same for weeks.”

The Times list is hand-curated; not an actual leaderboard of national book sales. As kids, we assume things are what they purport to be. But the list felt to Banister like a kind of deception. “The more we understand about how the world works,” Banister explains,” the less childlike we become.”

By this standard, Banister—in her red plaid button-down (a pattern picked for her by her nine year-old son), flowy pink pants, and no fewer than three necklaces—is a conundrum. She knows a great deal about how the world works and yet here she is, fluorescent against the grey day, sitting under a giant, one-of-a-kind piece of Hello Kitty art.

And she’s always learning more.

She explores the world with wonder—not afraid to play, to make mistakes, and to say “yes, and” with the commitment of an improv performer. Once, while touring Paris, Banister saw a line of people waiting outside the Notre Dame Cathedral. Curious where they were headed, she joined the line’s end.

Banister: Sometimes when I see lines in public, I get in them to find out where they’re going. It’s just fun.

KG: Doesn’t that put you at risk of following the herd?

Banister: I’m not in line the way other people are in line. They have a reason to be there. I don’t.

As she wound her way to the front of the line, she heard choral music emanating from the depths of the cathedral. “The space was built for people to come find refuge in the darkest time,” she says, recalling how she was moved to tears by the mass. “I felt very humbled by that.”

Banister’s love for monumental works of art—whether choral music, giant Hello Kitties, or the Taj Mahal (“a symbol of love and devotion and hope”)—leave her both humbled and humble.

She doesn’t name drop.

She doesn’t brag about her returns.

She doesn’t even bring up her portfolio companies without prompting.

She could be forgiven if she did. Her storied track record includes angel investments in SpaceX, Uber, Thumbtack, Postmates, Opendoor, Affirm, Carta, and Niantic.

Along with her husband and long-time business partner, Scott Banister, she boasts more than 170 portfolio companies. The pair was recognized by TechCrunch as the 2016 Angels of the Year and they topped the Crunchbase Angel Leaderboard for 2010-2020.

In 2016, she joined Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund as its first female investing partner. Today, she leads Long Journey ventures alongside Lee Jacobs.

She is one of the valley’s pre-eminent angels. But she’s more comfortable talking about her hero Bill Murray (“when you seek to become enlightened, enlightened people just appear to you”) or about her fascination with Japanese sex clubs than she is about her success.

Banister lives life on her own terms.

Her myriad social accounts attest to this, reading like the journal of a time traveler from the early days of the internet—idealistic, open, and often oddball random. She’s tried nearly every platform at least once: Internet Relay Chat (IRC), Myspace, LiveJournal, Posterous, Flickr, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Quora, Medium, a blog/TV show on TechCrunch, Producthunt, Substack, Callin, Clubhouse, Popshop Live (a portco), Youtube, and of course, Twitter, where she says she tweets “as if no one reads it.”

Baby Got Back comes *back* again and again:

The only platform she has never been on? Tik Tok. And don’t hold your breath for her to join anytime soon, she says.

China will take over the world. We’re doomed.

–Banister

Some people don’t take her seriously because she’s weird. But that doesn’t bother her too much: “I get to be a Trojan horse,” she says.

But most people whom she encounters like her—”like a flame to moths,” her husband Scott says. Cyan Banister suspects it’s because she reminds people of something they’ve lost.

“Everyone wants their childhood back,” Banister says.

Banister’s childhood, though, was unlike just about anyone else’s. At the age of 14, she became homeless after her mother sent her on her way with $20 and a note reading “good luck.”

She dropped out of high school and learned to survive on her own—panhandling, dumpster diving for food scraps, and washing herself in public fountains.

Over the course of 40-some jobs, mostly low wage, Banister became a self-taught systems administrator, moved to Hong Kong for work, moved back, and taught at-risk women to code. Eventually, she worked her way up the ladder at a cybersecurity startup called IronPort, which was acquired by Cisco in 2007 for $830 million.

Her first big exit check in hand at age 30, she could have kicked back, content to have achieved success in her decade-and-a-half career that most can only dream of in a lifetime. Instead, she decided to invest (incinerate is another word that starts with I) almost all of her hard-earned payout into a risky, highly untested space company called SpaceX.

I blew up [my nest egg] on a rocket ship.

–Banister, Science and Saucery

After leaving IronPort, she founded a company called Zivity that paid photographers and models to post pin-up photography online—an OnlyFans before its time. She even posted nude photos of herself to promote the platform, earning both ire and respect.

She was then tapped to join Founders Fund where she pushed contrarian bets—even by the standards of the fund—and went toe-to-toe with her feared boss, Peter Thiel.

DS: Why did you feel comfortable challenging Thiel when no one else did?

Banister: [laughs] He couldn’t do anything to me! What was he gonna do? Fire me? I don’t care.

If Banister is unbowed by the ravages of adulthood, it’s at least in part because she’s been thinking—and living—different for more than forty years.

In the beginning, convention simply wasn’t an option.

ORIGINS: In which Cyan digs holes

Cyan Banister—born Cyan Starr Callihan in 1977 (the year the first Star Wars came out)—grew up on the Navajo Indian Reservation.

She lived near Canyon de Chelly, the home of ancient Anasazi ruins and of Spider Woman, the matriarch of Navajo legend who uses her powers to protect the Navajo people and eat misbehaving children.

It was fertile ground for an imagination like Banister’s.

She would play all day long in the Arizona desert with her sister, Christian (born Heather)—five years her senior—and her dog Cleo, who was like “another sibling.”

When her sister started playing with friends her own age, Banister took to solo world-building and carved out little holes in the big desert. When rain clouds filled the sky, her holes would fill with water and transform into Cyan-sized pools.

She loved to sit in them.

Arizona storms are magical, so we’d often have streaks of lightning across the sky and the smell of the water hitting the dirt was like nothing else in this world. That was my happy place. Still is. I dream about heading to Arizona during the rainy months, grabbing a mattress and just laying outside somewhere.

–Banister, The Ugly Duckling

Banister felt things very deeply.

She sometimes used crafting to express her feelings. For example, she demonstrated her love for her grandmother by turning paper into elaborate floral arrangements and giving them as gifts to her grandmother, who lived nearby her family’s trailer. She delighted in the joy they brought her.

Banister crafts to this day—she likes to knit, make homemade fashion, and paint.

Other than from her grandmother, though, young Banister didn’t receive a lot of affection.

The kindest words she can remember her mother saying to her during her entire childhood: that her birth had been “planned.” Banister remembers driving a long distance one night in her mother’s truck and falling asleep on her lap.

I remember feeling so very happy. It's also the only memory I have of her touching me. Of course, she wasn’t even doing that. She was allowing me to be there as she drove.

–Banister, The Ugly Duckling

Banister’s sense of abandonment shaped how she learned to relate to other people. In her teenage years and twenties, Banister sought out affection in the form of relationship after heart-rending relationship. “I was really in love a lot,” she says. “I was so angsty.”

Banister is not currently in touch with her mother except via occasional text.

When I held my son for the first time, something came over me. I felt so protective of him. It was instinctive. My only guess is that [my mother] struggled with mental illness.

–Banister

Banister is writing an autobiography in installments on Substack. She writes about her younger self with raw emotional connection—not the detached knowingness of adulthood. Her trials, tribulations, and traumas land with an urgency that would make Laura Ingalls Wilder proud.

It’s called The Ugly Duckling.

The name comes from Banister’s mother. When things didn’t go well for her at school, her mother would remind her that she was different—that she was “an ugly duckling.” One day, her mother told Banister, she would become a swan.

Banister felt different from other students at her school. And not just because she was white (or as she thought of herself “a pale Indian”) and they weren’t. She was quieter than her peers, and didn’t start speaking until much later. Her mother believed her muteness was the result of brain damage after a difficult birth.

Banister took to observing everything around her.

People thought I wasn’t smart, and I used that to my advantage. You didn’t need to be the smartest person in the room, but you did need to pay attention. I understood so much more than people around me thought I did and my mind was always at work. Even today, I sit in board rooms or meetings often quiet. I say very little, but when I have something to say, I try to make it matter.

–Banister, The Ugly Duckling

Another source of difference: Banister’s relationship with her gender. “I never felt like I fit in with the other girls ever,” she remembers. She says that her experience with Zivity helped her understand more about the fluidity of gender and sexuality.

In 2016, she came out as genderqueer in Wired.

I didn’t feel like I was a tomboy. But I embraced it. I would tell people “I’m just a tomboy,” but that wasn’t true either. None of the things were true.

–Banister, Wired Magazine

Throughout the difficult years to follow, Banister would find refuge in her mind—stealing away to her imagination whenever she could. As she grew up, she lost her ability to control her daydreaming, and was diagnosed with ADHD.

The backdrop was a peripatetic childhood. Banister’s mother pursued multiple graduate degrees and relationships (including one which gave Banister a baby half-brother), with little Cyan in tow—more, she suspects, to take advantage of government benefits available to low-income families than anything else.

From an early age, Banister could feel complicated dynamics bubbling beneath the surface in her family—a mystery conflict between her mother and her kindergarten teacher, a fist fight between her grandfather and her father (thereafter absent from her life), and the disappearance of pets with no explanation.

We had a habit of things just happening, so you just accepted it and moved on.

–Banister, The Ugly Duckling

There was never enough food in the house. Banister went long periods subsisting on candy, which would in turn further affect her ability to focus in school. Her performance suffered despite the fact of her natural intellect. Early on, she scored in the 99th percentile on all of her tests.

Soon, a deleterious cycle started: Banister would run away from home. Then the police would pick her up, and return her to her absent mother. At the age of thirteen, she experienced homelessness for the first time. When she was fourteen, she became homeless full time.

LEVELING UP: From the streets to San Francisco

On the streets of Arizona, Banister had to learn to fend for herself.

She tried to get jobs, but turned to panhandling when no one would hire her because of her lack of a high school diploma and experience. This struggle paved the way for her later opposition to the minimum wage.

I would have happily scrubbed toilets for $1/hour. That would have kept me from sitting out on the streets and panhandling.

–Banister, Canceled Podcast

Her panhandling days came to an end when she asked for money from a man carrying a baby in his arms.

“I’m sorry,” he told her, indicating his baby, ”I need to save my money for her.”

Banister decided to find another way to support herself—and shake the shame of taking money from other people.

So what is success? Well, I define it as being self-sufficient. That’s it. Some people define it as simply just being happy, because some people are incapable of being self-sufficient.

–Banister, The Ugly Duckling

Various parents in the Flagstaff community took her in—including a high school classmate’s mother and an ex-boyfriend’s mother named Karin. Karin taught Banister many of the essential skills and values her biological mother did not. She charged Banister rent of $200 a month, which Cyan credits for helping her learn the importance of making a living.

In order to make rent, and unable to get a low-wage job, Banister started her first entrepreneurial ventures. She picked up free books at donation sites and sold them to local bookstores. She later expanded the strategy to donated clothing.

Eventually, someone taught her to make necklaces—a big step up. Banister went from earning a dollar or two per transaction to earning $20—what she calls a “life-changing amount.”

Then, for the first time, her deep personal interest led her to a market opportunity.

British punk rock groups had developed a following in the United States, but their marketing arms lagged behind, leaving space in the market for an unofficial manufacturer and distributor of merchandise. Banister filled the role—learning to screen print t-shirt designs and make patches with logos and lyrics from the groups.

Her business was also the catalyst for something even more life changing than $20: her first encounter with a computer.

It started with a chance meeting in Tempe, Arizona, where she was living.

A young man named Chris had purchased a large patch of Banister’s to wear across the back of his favorite green army jumpsuit. He wore it to high school every day paired with—what else—a gas mask. “Be warned: the nature of your oppression is the aesthetic of our anger,” it read, a quote from Crass, his favorite British Punk Rock group.

One day he was going down the street in Tempe and passed a girl sitting on the sidewalk (which was considered illegal loitering).

“Hey! I made that,” the vagrant yelled at Chris.

“Made what?” he asked, stopping.

“That patch on your back.”

“Prove it. If you made that patch on my back then where did it come from?”

“Eastside Records,” she replied with certainty.

She found out his name was Chris, and he gave Banister his number. A few weeks later, she saw him in a cafe, Java Road, sitting “by the glow of” his laptop.

“You never called,” he said. “Wanna see some anime?”

After watching with him for a while, she asked, “Can you get online with that thing?”

Her life would never be the same.

I knew instantly that that was what I wanted to do. It was like a bit flip. It was over. That was my calling; that was what I had to do. Nothing else mattered to me at that point.

–Banister, The Education of Millionaires

Her newfound interest occupied her life. Working as an administrative assistant at a company that sold and installed fire sprinkler systems in commercial buildings, she used the company’s fax connection to link up to the online world she loved, under the cover of her screen name.

Cyanide Death, Strychnine, Doom (after Doom the band, not the game), Dystopia (“the crusty hackerperson”), Starr, and, of course, Cyantist—Banister’s teen years were marked by shifts in identity. Names given to her on the street morphed into internet handles—internet handles became a life.

She quickly got bored at the sprinkler company.

Question: What is the most important thing someone has ever said to you?

Answer: Being bored is an insult to your intelligence -- My sister.

–Banister’s Quora

Banister turned her boredom into productivity and learned to code a database for the company. Now, every time someone asked her to check the company’s stock of a given item, she could do it from her desk.

She describes this period of her life as a video game—always trying to get to the next level of pay.

When she was homeless, she says, she blamed her position on capitalism, thinking, as did many of her friends at the time, that greedy businesspeople were robbing it from everyone else.

But as Banister began leveling up, her views changed. She started to develop a sense of purpose and pride that came from serving other people and providing for herself.

She is now a cheerleader for all things capitalism and entrepreneurship. Today, she identifies as an outspoken libertarian. She donates to causes including marijuana legalization and sex-work legalization and is a leader in the movement to recall Chesa Boudin, San Francisco’s liberal district attorney.

After the sprinkler company, Banister took another step up the ladder, this time landing a job at an internet service provider, where she provided dial-up tech support.

One day, her manager plopped a book down on her desk: Essential System Administration, by AEleen Frisch. This, she was told, would be the key to leveling up in the world of tech support. She was intrigued, but her aversion to being told what to do by an authority figure left the book sitting on her desk, unloved.

Her job was not exactly a salve for boredom, though. The main question she asked callers: “Have you tried rebooting your modem?”

In her spare time at the job, she registered domain names. She had fun doing it, until the bag of bills arrived to pay for the registrations. She would later bond with her husband-to-be over their shared love of registering domains.

One day, no doubt remembering her sister’s maxim about boredom, Banister finally cracked open the book. One page changed her life.

She read the instructions on the page.

She thought about what they meant.

Then she synthesized her learning with remarkable speed, changing her boss’ root password in the process.

She proudly went to his office, new password in hand, to reveal her discovery. Instead of firing her for breaching the company’s system, he gave her a promotion—choosing to reward her initiative. Now she was a systems administrator, and soon she would become a manager.

Beep boop: novice to expert.

Her love for technology—and a man—soon brought her to San Francisco, just before the turn of the millennium. There, she found a job working in systems administration for NBCi—NBC’s early attempt at an internet portal and homepage.

After a month-long stint in Hong Kong, where her coworkers pranked her into eating a bird’s nest (yes really) she worked at the Women’s Economic Agenda Project in San Francisco, teaching formerly incarcerated women IT skills. Many of Banister’s student were not even literate in English, let alone UNIX.

From her class of several dozen students, only two finished.

To watch these women struggle...It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done. Every single one of these women in my class had been raped or gang raped. Every single one….Probably the proudest thing [I’ve ever done in my life.]

–Banister, Science and Saucery

By 2003, Banister started at IronPort Systems. Its flagship product was IronPort AntiSpam, a spam filtering service. For a cybersecurity expert like Banister, there could have hardly been a better place to end up.

She began as a standards and practices manager, but Banister was soon offered promotion after promotion. With each step up the corporate ladder, instead of more money, Banister negotiated for more equity.

She rose through the ranks to become a senior security operations manager, where she says she “oversaw the world’s largest known spammer blacklist.”

In addition to her blazing-fast rise through the ranks, two other major events from her time at the company launched her to the next level. In 2007, Cisco acquired IronPort for a whopping $830 million, her first liquidity event.

She also met her husband, Scott Banister, who was one of the company’s two co-founders. Scott—who is even more of an introvert than his self-described introverted wife—was at this time a successful angel and entrepreneur himself.

After dropping out of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign’s computer science program (the powerhouse program also pumped out Luke Nosek, Max Levchin, and Marc Andreessen in the 90s), Scott Banister co-founded a company called Submit It! which was acquired by LinkExchange which was then sold to Microsoft.

From there, Scott Banister launched his angel career with PayPal, where he was the first investor and board member (he is also listed as a developer on PayPal’s patent). PayPal Mafia companies led him to his first series of successful venture deals.

Scott Banister first appeared in Cyan’s blog in June 2005.

I have a new love in my life. How he came to be in my life is complicated but it was worth it. We have great energy together and we just “are”. It doesn’t take much effort to have a good time. The other day we were out with some friends one of them mentioned that we seemed very serene which was a contrast from my last relationship.

–Banister, Journal of Cyantology

“Complicated,” Cyan Banister says, was a reference to the fact of their working together at IronPort. Additionally, she met him in the midst of a series of open relationships.

Being polyamorous was not her dream, she explains. Rather, it was a way of coping with how deeply she felt about her partners. Her long-term, monogamous relationships always seemed to end in heartbreak, and each time she felt as though she had wasted years developing a connection and getting to know someone—with little to show for it.

Open relationships were a way to “speed things up a bit,” she explains, “basically like an MVP strategy for dating.” And “it worked. Until it didn’t.”

Scott and Cyan tied the knot roughly a year after meeting, in a Las Vegas ceremony officiated by none other than an Elvis Presley impersonator. Scott came into the relationship with a then three-year old daughter. Together, they have one child of their own and four chickens.

[Our Las Vegas ceremony] was awesome and perfect in every way. We felt like young teenagers running away from our parents to elope in the middle of the night. Now that’s romance!

–Banister, Journal of Cyantology (2006)

They also celebrated a second wedding ceremony in Brussels for the benefit of Karin—Banister’s adoptive ‘mother’. She moved there after leaving Arizona. Karin’s Belgian neighbors pulled out all the stops. One even dressed up as Jesus to perform the ceremony.

Having Jesus officiate, Karin reasoned, would be her only hope of outdoing Elvis.

An angel gets her wings

The year following their marriage, IronPort was acquired. Banister found herself unsure what to do with her pile of cash. Maybe, she thought, she’d invest it in real estate or the stock market. But her husband suggested that she risk it all on early-stage startups. So she asked around and found SpaceX, thanks to the couple’s extended PayPal network. She was told that the company would be as close as she could get to a binary outcome.

It was the first step in a fifteen-year collaboration. Over the coming years, Scott, who had been investing since turning 18, would teach her the ins-and-outs of the venture business. He respected her intelligence, she says, and pushed her to be the best she could be.

One of her favorite movies of all time is The Founder, which depicts the founding of McDonald’s. She loves this movie because it shows characters staying up until all hours of the night discussing business. The women in the film are respected for their intelligence, not their bodies.

This, she says, is true romance.

For their part, the Banisters’ partnership works because they are able to combine their respective strengths. Cyan is an empath who relies on intuition. Scott, meanwhile, is more interested in quantitative analysis. His focuses are “legal, politics...and complex later stage financing.” She says that he “loves” looking at term sheets.

While he has worked to cultivate his network, anchored by the PayPal Mafia, she has historically focused on bringing new founders into the Banister fold.

They work under the name Banister Capital.

I called it Banister Capital because it got me into events. It’s funny, because if you’re an angel investor you don’t get invited to a lot of things, but as soon as you put the word “capital” at the end, they’re like ‘ooh, that’s legit.’ And suddenly, I was on panels....It’s a little bit of a hack.

–Cyan Banister, The Full Ratchet

After SpaceX, Cyan Banister’s second investment was in Topsy, a social media indexer. Vipul Ved Prakash, Topsy’s co-founder, had worked at IronPort competitor Cloudmark. Banister says that her and Prakash were “frenemies.” But post acquisition, they reconnected.

Topsy was acquired by Apple in 2013 for a reported $225 million.

The Banisters maintain an evergreen investment strategy. Whenever they have successful exits (which they do a lot), they put the money right back into the ecosystem.

Zivity

When she was little, Banister’s mother kept a book of ancient Chinese erotic sculpture around the house. “They were hardcore,” Banister remembers.

In awe of the book, she brought it to school to show her friends.

I’ve always been interested in how beautiful our bodies are.

–Banister, Zivity Blog

When our conversation inevitably swings to Japanese sex clubs—“I’m interested in the way power dynamics between men and women have been shifting in Japan”—she pulls out a blazing pink book coffee table book by the photographer Joan Sinclair. It depicts the impossible-to-access world of these clubs.

She has been gifted the book eleven times (so far).

She opens the book to a page picturing a “groping train”—a simulation of a subway car where men can pay to grope women. “I mean, I guess if they have the urge this is a better way of dealing with it,” Banister says, turning the page.

In her vision of the world, people are more open about sex. “I’m a little more libertine than a lot of people,” Banister told the Wall Street Journal in 2017.

Zivity was a step in that direction. The platform paid models and photographers to post their content—creators with the most upvotes would get larger payments. The daughter of two artists, Banister also wanted to create something beautiful.

There's a huge gap between the Disney nature of free sites driven by advertising and pornography that fascinates me. The land of HBO and Showtime. I'm driven to create products that allow creators of this content to connect in meaningful ways with their fans and monetize their work as well as their brand.

–Banister, Zivity Vision

When she decided to leave IronPort to start Zivity, Banister thought she had the perfect source of funding lined up—her exit check. But Scott had other plans.

He refused to allow us to personally invest in Zivity until my co-founder and I raised the first half of our first round ourselves.

–Banister, Quora

For a first-time founder like Banister, Scott felt that the experience of raising a round herself would offer crucial learnings. And it did. It took more than fifty pitches for her to get her first yes, ultimately from Luke Nosek, a PayPal co-founder.

But not everyone approved.

Some IronPort colleagues were even less pleased. She recalls a former supervisor picking up the phone to yell at her. When Scott Banister joined Zivity as a co-founder, many people were mad at Cyan, feeling that she was responsible for Scott’s involvement in what they derided as a “porn platform.”

Banister wanted to post her own nude photographs to the site in order to promote it, but with these comments ringing in her ear, she felt nervous. She felt comfortable enough with the idea of the photos being seen. But she was warned that people in the industry might no longer take her seriously.

So she turned to her friend and mentor Penn Jillette—one half of the acclaimed magician duo Penn and Teller—for advice.

Penn told me that if I didn’t [post the photos], I would be letting the assholes win.

–Banister

And so she did.

The reaction caused her virtually no harm—in fact they earned her positive press coverage. The narrative: Banister was a founder who believed in her product enough to take an enormous personal risk to promote it.

Zivity lived for ten years, teaching its founder a multitude of lessons along the way. Ultimately, Banister burned out and started working on other things (including jobs at AngelList and Founders Fund) before finally closing the company’s doors.

She sent a closeout email with her learnings and threw a party to mark the end of an era.

A few months ago, I talked to someone over a video chat that I had just met, and he told me how much he admired the site. When I confessed to him that I was going to shut it down, he said, “You had an amazing run.”

Up until that point, I didn’t think of it that way. I thought of it as my own personal failure.

However, he is right. We had a good run. Zivity helped change what people thought was impossible. We were the first among firsts for many things. We pioneered a lot of crowd funding, we normalized this form of art a little more, we nurtured and helped many artists, we met many of our patrons/fans who keep the engine of art humming…

Once the dust has settled, we’d like to hold an event to celebrate the end, or at least the end for now. I’m keeping the Zivity domain name and may pursue this again someday in a different way…

–Banister

INVESTMENT PHILOSOPHY: “Everything I do is a waste of time.”

Banister’s investments are driven primarily by her intuition. Her intuition is shaped in two primary ways: market discovery and people.

Step 1: Going deep on markets

I love short-lived habits, and regard them as an invaluable means for getting a knowledge of many things…

–Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science

I go deep down the rabbit holes of market problems that I want to invest in.

–Banister

In 2012, a new kind of game entered the scene, using AR to get its users out into the world. Its tagline: “It’s time to move.”

Banister got into it. Like really into it.

A core group of friends and I are super into it...we go out on these crazy missions, there are some people who rent boats, there are some people on the team who fly all over the world to play this game.

–Banister, TechCrunch

By playing the game—called Ingress—Banister came to understand firsthand just how much of a pull it had for users.

She had spent nearly two years researching AR and VR, meeting nearly every founder in the space. But she hit a dead end, finding herself “bummed” with the state of the industry. “There were a lot of false starts,” she explains.

This research gave her the background knowledge to appreciate just how differentiated Ingress was. After playing the game, she looked into the company and discovered that its maker, Niantic Labs, was owned by Google—another dead end. But in 2015, Google spun out Niantic Labs as its own company.

It was time to move fast.

She back-channeled through the founder of Hint Water, one of her portcos, to get to John Hanke, who is now one of her favorite all-time CEOs. “I want to work for him so much it almost hurts,” she tells us.

They almost got me. They have a desk there waiting for me, but I’ve promised my family I won’t do it.

–Banister

When she put her check into Niantic in 2016, the company was valued at $150 million.

Later that year, Niantic released Pokemon Go, which became an instant hit and is now played by more than 150 million people worldwide. And as of the company’s 2019 series C, Niantic was worth $4 billion. In 2020, its user numbers and revenues reached higher heights than ever.

Banister’s Niantic discovery exemplifies her user-first approach: While she engages in deep research into markets—here in the AR/VR space—she was led in her exploration by deep personal curiosity.

Her pursuit of these interests often sees her joining metaphorical lines. “Everything I do is a waste of time,” Banister jokes. Her game playing, for example, or her extensive use of social media, or shopping, or her recent interest in trading cards, would not be considered by many other VCs to be a strictly efficient use of time.

The first hour of my day is a nightmare.

–Banister

Banister’s “short-term habit” pursuits put her in position to reap long-term rewards.

Because I’ve experienced these markets as a user, I can respond authoritatively in meetings to different ideas. This gives me an advantage and really impresses people.

–Banister

In her market exploration, she also relies on conversations “with smart people that [she] respects.” This is one of the reasons she was excited to join Founders Fund. It’s also the reason that she maintains relationships with engineers and designers more than other VCs—they’re the idea generators. Plus, she says, her VC friends “don’t get to let loose.”

Even following her initial investments, Banister is continuously engaging with her portfolio companies in her own, immersive way.

She speaks with every Uber driver she meets.

She set up an online store with Cashdrop to sell blood oranges from the citrus farm that she owns in Southern California, Holy Guacamole Farms, and hand delivered them to each customer, asking them how the experience was (it and the oranges were good—KG can attest).

In addition to following her own curiosity wherever it may lead, she makes an effort to see how other people—particularly her kids—react to different products.

It’s important to live in the world in which she is investing, she says. To this end, she lives in a “normal” house in San Francisco (one of the city’s classic Victorians) located in a socio-economically diverse neighborhood. She shops at Walmart whenever she can, and she maintains friendships with people who are not high net worth.

If you invest in things people use, then you have to live that way. Otherwise, you start investing in edge cases.

–Banister

Maintaining this perspective has led her to investments that were overlooked by other VCs.

Sheertex, for example, is a Banister portco that makes “The World’s Toughest Pantyhose.” Other VCs passed. ‘Who,’ they wondered, ‘wears pantyhose anymore?’

That’s a really elitist view. Many people still have to wear pantyhose as part of their uniforms—nurses and flight attendants, for example. The market opportunity is actually enormous.

–Banister

She also likes Wish.com, which is a company in the Founders Fund portfolio (not one of hers). She thinks of it as an anti-elite play.

[other VCs] asked: ‘why would anyone want to buy super cheap shit online?’ But then, the Dollar Store shouldn’t exist. There’s an entire market that shouldn’t exist.

There are a lot of people in America for whom Amazon is too expensive. We should be serving them too.

–Banister

Banister has come to appreciate how her own background informs her unique perspective.

Question: “Hi Cyan, Wow I’m amazed by how much you have accomplished - What are you most proud of?

Banister: My lack of a formal education. I fell in love with technology at an early age and I’m self-taught. Thank you btw.

–Banister, Producthunt

Step 2: Discover and evaluate founders

The next step in Banister’s process: finding founders. When Banister Capital was starting out, her purview was discovering out-of-network entrepreneurs.

She attended every conference and every party she could get into—this is where the Banister Capital name came in handy. She also went to her friend Jason Calacanis’s pitch nights and his Open Angel Forum.

Now, she says these events have become overwhelmed by VCs and are no longer as useful. With a larger network, she is also able to rely more completely on warm intros.

Once the intros are made, or the companies pitched, Banister must evaluate the founders. This, she says, is the most determinative part of her decision-making process; more so than product or market considerations.

In the end, her judgement relies on a two-part test:

Is this the right person to tackle the problem? Are they obsessive about solving it and do they have the right personality to tackle the given market? Travis Kalanick at Uber is a great example–more on him later.

Do I want to drop everything and work for this person? Ie. do they have the charisma and capacity to sell me on the given product and the vision? Can they explain the company succinctly? Do they inspire me to want to fight for them? If the answer is yes, Banister says, then the founder will have greater success in convincing other investors and potential employees to join their cause. She believes in investing in companies that will fundamentally change human behavior. In order to achieve this, founders “need to be crazy,” she says,” but in a good way.”

She never Googles founders before she meets them. That way, her evaluation is “raw [and] unfiltered” by the image they try to project of themselves online. And when she’s in the room for pitch meetings, Banister uses the time before the pitch—which she says other VCs too often waste on small talk—to get a better sense of who they are as people.

She starts by simply asking them to tell her their story.

Often what they do is they tell you a story of resilience. Maybe they’re a founder who came from Pakistan and they came to America and the journey to get to America is incredibly hard. And so that shows grit...Or they were on the streets themselves, or they put themselves through college.

One of the things I am looking for is overcoming hardship, overcoming some kind of struggle that someone had.

–Banister, The Twenty Minute VC

Banister understands how hardship can shape someone for the better.

Circumstances in my life were not good and a lot of it was indeed outside of my control. I didn’t get to choose the parents to which I was born, the shelter in which I lived under or the eating conditions I had. However, I did get to choose how I felt about all of it.

–Banister, The Ugly Duckling

Banister then wants to understand how a person’s life circumstances lead them to want to solve the problem they’re working on. She thinks it’s important to decipher whether passion is real or whether founders are in it for the money. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to make money, she says, but on its own ”that’s not enough.”

Just like lining your wallet with more cash—I mean yeah, it’s a motivation, but at the same time it’s not going to excite other people around you, and it’s not going to make you the best person at running a company.

–Banister, This Week in Startups

If she is meeting with a co-founding team, she wants to understand how they fight. Do they have a history together? How have they resolved conflicts in the past? It’s one reason that she likes seeing family teams and married couples who go into business together.

Making these determinations can be done in the course of an hour, she says. It’s one reason that she’s able to move so quickly.

Sometimes, Banister meets founders who are not working on investable problems yet. In that case, she enters them into her “mental rolodex.”

For example, when she first met Marco Zappacosta, the founder of Thumbtack, he didn’t mention that he was working on a startup. They crossed paths at a fundraiser in Los Angeles where Zappacosta approached Banister. He had heard of her work and wanted to say ‘hello.’

I was like ‘what a bright, awesome person.’ I’ll file that away!

–Banister, This Week in Startups

She next encountered Zappacosta at a dinner hosted by Jason Calacanis, where Zappacosta was pitching Thumbtack. Remembering her positive impression of him, she texted Scott right away, describing Thumbtack as the “OpenTable of professional services.” Scott was on board and she swiftly wrote Zappacosta a check.

Another notable occupant of Banister’s mental rolodex: Pete Buttigieg, who Banister met on a VC ‘Mid-America’ tour before his 2020 run for president.

Her libertarian politics don’t exactly make her and center-left Buttigieg a natural match. But when the tour stopped in South Bend, Indiana, where Buttigieg was mayor, she immediately noticed the difference between South Bend’s leadership and that of the other cities they stopped in. It was “night and day,” she says.

She first met him in a cafe, talking to constituents. She was impressed with his gravitas. “He addresses everybody with dignity,” she says. When she asked South Benders whether or not they thought Buttigieg was going to run for president, they told her, “We hope so!”

I get paid to see abnormalities in the marketplace. Pete is an outlier. I knew the moment I met him that he was going to be president one day.

–Banister

Other politicians give platitudes, but according to Banister, Buttigieg “never gives bullshit answers. He’ll tell you he needs to get more information if he’s not sure of an answer.”

She also appreciates that he served in the military. She thinks it would make him think more critically before entering military conflicts.

Banister was so smitten with Buttigieg that she tried pitching Founders Fund, the elite VC firm founded by Peter Thiel, to open an office in South Bend.

–Vox

Step 3: Putting it all together

When her founder intuition intersects with her market intuition, Banister is ready to pull out her checkbook.

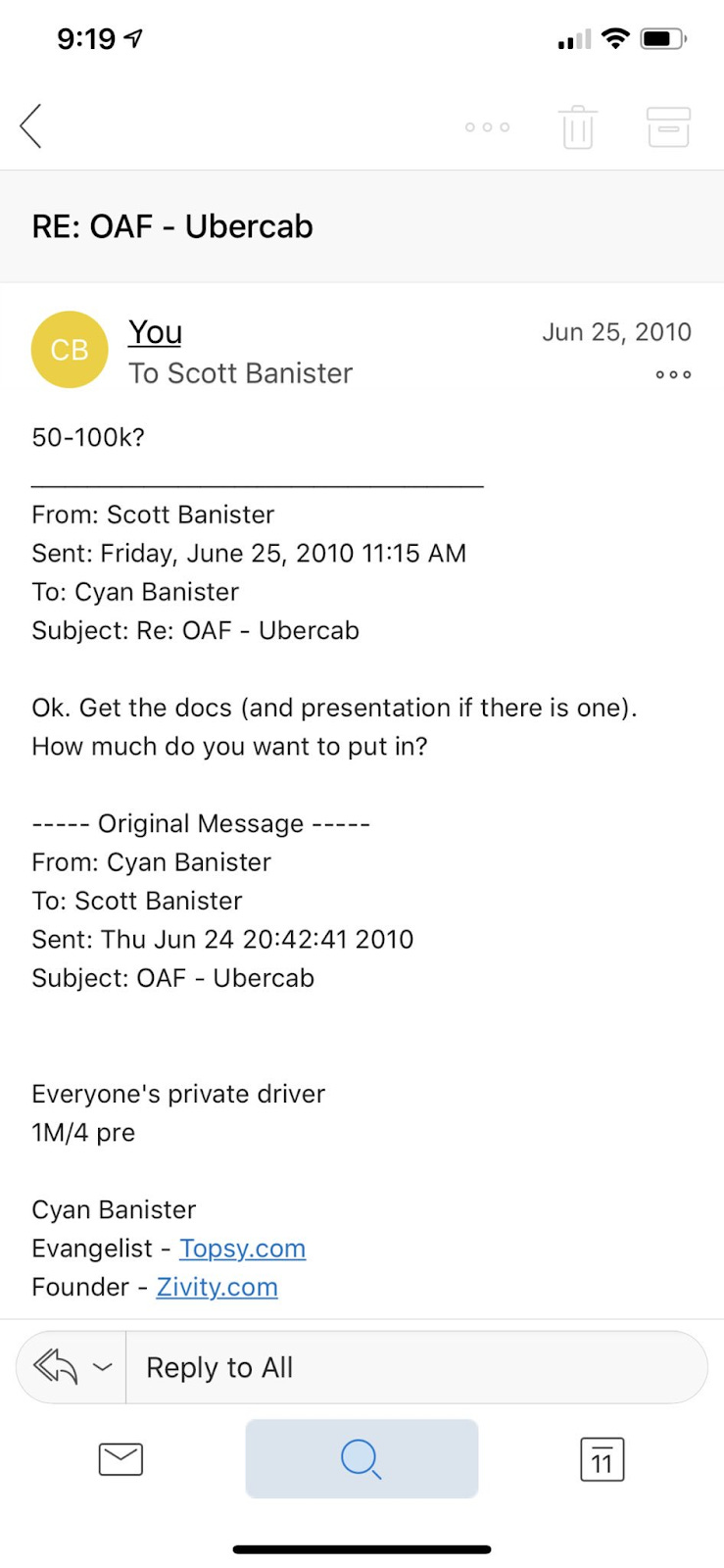

Her $50,000 investment in Uber is a prime example.

Her understanding of the market problem—that the taxicab industry was ripe for disruption—grew out of her political involvement. At the time, San Francisco had less than 1500 taxi medallions for a city of more than 3 million people.

The libertarian circles in which Banister traveled had long been decrying taxi medallions. To them, the cap on taxi medallions was a clear example of government meddling in the market. They saw a protectionist racket leaving consumers stuck with high prices and subpar service.

She looked into the problem for years, but decided that the industry was too entrenched to solve the problem.

Cut to a routine moment: Banister was picked up by a contracted chauffeur, Roger, to take her to the airport. He was in the first group of six drivers employed by a new company called UberCab. Roger suggested she look into UberCab and gave her then-CEO Ryan Graves’ business card.

Seeing that Graves’ number had an out of region area code—Chicago—Banister was skeptical. She and Scott strictly limited their portfolio to local companies.

The next few times Roger picked her up, he told her that his Uber business had grown so dramatically that he had recruited nearly a dozen friends and family members to drive for the service—and again recommended that she call Graves.

But still she didn’t call.

Separately, she met a brash, young entrepreneur named Travis Kalanick in the lobby of her hotel while attending a conference hosted by David Hornik in Hawaii. She was struck by his aggression, and made note in her mental rolodex that he would be the ideal founder for a problem requiring an aggressive personality.

I basically said here’s an aggressive person who has a lot of gravitas—people listen to him. He’s on the bench—that’s interesting. File that away as an investor, that’s it.

–Banister, This Week in Startups

Her knowledge of the problem, her awareness of the company, and Kalanick’s place in her rolodex all converged at Jason Calacanis’s Open Angel Forum in 2010. There, Kalanick pitched the company. At this point, he was an investor in the company standing in for Graves, who couldn’t make the conference.

Given her memory of his aggression and his demonstrated passion for the problem, she had doubts that Kalanick would allow anyone else to be the CEO for long. This, she thought, portended good things for the company.

She knew that in order to be successful, UberCab would have to do battle with the powerful and intransigent taxi industry. It would also need to take on the black car industry, and later, local governments.

The fight would not be for the fainthearted. When the food service Seamless attempted to expand into the notoriously mafia-controlled black car industry in New York, its CEO Jason Finger received a voicemail from a caller threatening his young family. “You’ve got such a beautiful family,” the voice said,” why don’t you spend more time with your baby daughter?” (as reported in The Upstarts).

Kalanick wouldn’t have to worry about that—he was a bachelor and a born fighter.

Banister moved on the deal with her typical speed.

The resulting deal closed in 2010. She invested $50,000 at a pre-money valuation of $3.86 million. Her stake was worth a reported $250 million by the time of Uber’s IPO in May 2019.

Banister is known for her quick deal-making. When her intuition is strong enough, she doesn’t even need to hear the entire pitch to make a decision about the company.

Her investment in Carta (formerly eShares) was another such case.

Her experience running Zivity gave her conviction about the problem (cap table management), and her intuitions about the founders led her to move quickly.

Speed represents one of Banister’s enormous advantages. It’s also one of the reasons she likes early stage investing so much. The ability to act quickly based on her intuition, without waiting for sign offs from anyone but Scott has, she believes, allowed her to secure many a deal before others.

It also ingratiates her to founders.

Ideals

Banister has a strong vision for the world that has guided many of her deals.

For example, Banister’s libertarian skepticism of large institutions isn’t limited to governments—she also recognizes the ways in which companies can become corrupted and wield outsize power coercively, despite their best intentions.

Google started out with the motto ‘don’t be evil.’ They are now the definition of evil….

Facebook took a turn for the worse—censoring speech. It’s become a place where people just scream about science.

–Banister

To this end, she looks for investments that decentralize industries. She likes that Uber took power out of the hands of the taxi and black car industries—and, as she sees it—into the hands of workers, who now have more flexibility.

Banister saw her work on Zivity as a play to disaggregate the pornography industry. OnlyFans, its spiritual successor, has achieved this goal with enormous success.

She’s also a proponent of decentralized finance. She describes herself as a “bitcoin maximalist,” and says that “it’s a store of value like gold.” She likes that it can’t be controlled by governments.

She believed in it so deeply, in fact, that Zivity accepted Bitcoin as payment. She wasn’t thrilled, though, when her team sold the Bitcoin early without her knowledge.

She doesn’t speak out on Twitter about Bitcoin, though.

Banister: I don’t want to have a target on my back.

KG: But aren’t you already a target for a lot of other issues?

Banister: I have to pick and choose who targets me.

Lately, she’s interested in decentralizing manufacturing.

I’m looking for an Alibaba of the Americas.

–Banister

Shameless self-promotion: Check out KG’s 24,000 word Alibaba report for a deep dive on the ins and outs of the business.

She likes how entrepreneurs can go on Alibaba and have just about anything made for them in small batches and in a matter of days. She wants to see something similar in the United States. (It’s worth mentioning, though, that Alibaba’s capacity to do this kind of manufacturing is reliant on a prodigious factory network currently nonexistent in the US. Perhaps 3D printing can help with this...).

She believes venture investing should be opened up to anyone who wants to invest. After all, she reasons, anyone can buy into public markets. She points out that a win with an early stage company would be transformative for most retail investors.

She advocates that the industry de-emphasize traditional accreditation in who it hires and funds. She also thinks that investors shouldn’t overlook older founders. Opening up entrepreneurship in these ways, she believes, would allow the industry to find more interesting and investable perspectives.

While she believes in opening the industry, she is a staunch opponent of identity politics. She says that “woke culture reminds [her] of the [Chinese Communist Party].”

She especially dislikes it when she perceives other women to be weaponizing their gender.

[cut in:] Sarah Lacy: Cyan….Do you think TechCrunch, do you think other blogs, don’t write about women when we fund great women?

Banister: Absolutely not. In fact I’ve seen nothing but red carpets for most women in our industry….I think we should celebrate individuals. I am Cyan Banister first; I am woman last. I’m sorry.

–TechCrunch Disrupt “Women in Tech” Panel

Failures

Banister is an avowed optimist—in life as in her investments. Several notable failures have provided her opportunities to temper her optimism with realism and to recognize red flags when they emerge.

GameCrush was one of her greatest disappointments. The company—which paired paying males with female gamers to play board games and video games. Other investors tried to get the company to go mainstream and limit the role of female gamers.

This attempt, Banister said, killed the company.

They killed their golden goose….Maybe becoming Twitch they would needed to become more mainstream, but it was a long way to go before they were Twitch and they had this amazing sticky audience that just loved the product.

–Banister, This Week in Startups

It was a $250,000 investment, which for her represented an enormous amount of conviction. Her typical deals were in the $50-100,000 range.

She noticed some red flags before making the investment, she says, but didn’t pull out. “A Banister always pays her debts,” she says, a reference to Game of Thrones. Since she had committed to making the investment, she was determined to follow through.

She changed that policy following her experience with GameCrush.

Another failure—one that took a tragic turn—was her investment in Ecomom, a marketplace for environmentally friendly products. Jody Sherman, the founder and CEO, took his life when the company went south.

She described it as a lesson in looking out for warning signs and making sure that founders get help when they need it.

No founder should get to the point where their situation that they’re in is worth taking their life. Period. All of us would have understood if he came to us and was like ‘I’m in over my head.’...We’re in the business of learning how to deal with shutting companies down.

–Banister, This Week in Startups

Finally: HQ Trivia. Banister was on the board of this live trivia game company. It enjoyed enormous traction at first, but collapsed amidst strife between the founders.

With early turmoil, Banister learned that other investors were pulling their term sheets, but she pursued the deal anyway, believing in the virtue of contrarianism. Here, she says, she learned that it is sometimes important to pay attention to signals from other investors.

She also now asks founding teams about their relationships with each other and how they resolve conflict.

BECOMING CYAN: Making the Big Picture

“Let’s go for a ride,” said Peter Thiel.

Founders Fund

They had just finished an offsite meeting together. Banister, at this point a one-year veteran of the fund, “felt terror” at the prospect of taking a ride with Thiel. It sounded like something a mob boss would ask.

“I have one piece of advice for you,” he began once they were on their way.

“You are really good at ‘I feel.’ I need you to get better at ‘I know.””

And with that they arrived back at the office. Thiel got out of the car and asked the driver to drive Banister the additional several hundred feet to her office door.

Thiel is an “amazing” teacher, says Banister. “He explains so succinctly what it is you need to do.”

She had just been the recipient of that exact type of feedback—which no doubt would have sent any mere mortal slinking away in terror. But Banister saw it as a backhanded compliment. “He thought I was very good at one thing,” she recalls, smiling.

It especially meant a lot coming from Thiel, not known for his warm praise. “He’s much more Laurie Bream than Peter Gregory,” she says, referring to the Silicon Valley character supposedly modeled on him.

He spotted very early the reason I ultimately had to leave Founders Fund. It was impressive.

–Banister

Taking his feedback, Banister tried her best to get better at the quantitative parts of the business—which, given the firm’s much larger, later-stage deals, played a bigger role during her time at Founders Fund than at any point in her career. The fund expected certainty; intuition wasn’t going to cut it.

A year earlier, Banister—the chronic outsider—had suddenly been invited to join the inside of one of the Valley’s most prestigious firms.

It was the ultimate level up.

I play life kind of like a video game and getting asked to work at Founders Fund was a dream come true. Because I idolized those guys. I look up to them so much. And being told that it was based on my own track record and my own experience and my own merits—that’s what I’d been working for my whole life.

–Banister, Science and Saucery

Banister doesn’t need approval, but she says it touches her when she achieves it nonetheless. One of the other most impactful moments in her entire career? Jason Calacanis telling her,” You can do it!” before she took the stage at TechCrunch Disrupt.

She scrupulously prepared for her interview with Thiel. She workshopped her answer for his famous question: “What important truth do very few people agree with you on?” But instead, he asked her: “What worries you?”

“It’s a great question to ask,” Banister says. “I told him that housing prices in the Bay Area worried me, in terms of the region’s ability to keep and retain tech talent.” It was a good answer: Thiel had been considering the same thing.

KG: What answer did you prepare for the standard Thiel question?

Banister: That men in Silicon Valley are more conservative than they let on in order to peacock for women. After I had been hired, I told him this. He didn’t believe me though [laughs].

Banister had anchored her worldview—this simulacrum of play and achievement—on her faith in her ability to accomplish anything. But at Founders Fund, Banister finally found the one thing that she couldn’t do: later stage investing.

She had thrived where her intuition could run wild; where her fierce independence and conviction won her competitive deals. Here, she had to work through the morass of sign offs, due diligence, and other roadblocks—sometimes from Thiel himself.

One memorable stand-off involved Niantic. After personally funding Niantic a month before joining Founders Fund, Banister advocated for the Founders Fund partnership to put $10 million of its own money into Niantic.

At the end of a meeting, the partners voted her proposal down. (“I’m going to be right on [Niantic],” she interrupts herself as she tells the story, eyes twinkling.)

“Alright, Thiel said, “so we’ll send them a pass email.”

But Banister wasn’t about to pass on the company. “I want to put in my entire subfund,” she announced.

Founders Fund allocates an amount for each partner to invest in a series of smaller deals, which they then earn super carry on. At this point, she had $30 million left in her subfund (out of an initial $40 million).

“Woah. Everyone sit back down,” he said, turning to Banister. “You can’t do that.”

“Why can’t I? One and done, I’ll focus on that one company,” Banister replied calmly.

“I don’t want anyone else to think this is acceptable,” said Thiel.

Flustered, he tried to negotiate her down, inventing a $20 million cap on subfund investments and then adding the stipulation that general partners would have to match each dollar one for one—re-introducing the need for sign offs.

“So a $40 million investment then?” she asked.

Banister went back and forth with Thiel, the rest of the partnership still watching, until she finally asked: “What is the most I can do?”

“I need you to keep investing,” Thiel said, conceding, “and you’ll need more money for that, so how about 15 and half goes into the main fund.” Her initial proposal of a $10 million investment from the general partnership had grown into a $15 million investment—split between her subfund and the general partnership.

“This is a one time deal just for Cyan,” Thiel told everyone else in the room. “No one else can ever do this again.”

Banister smiled at the memory. “People don’t know what to do when you have that level of conviction,” she says.

Though being hired at Founders Fund meant a great deal to Banister, she didn’t stake her sense of self on her position there. And for that reason, she says, she was comfortable taking bold stands and going head-to-head with her boss.

In 2020, after four years at Founders Fund, Banister left to return to her beloved angel deals.

I’m dyed in the wool early stage. I’m addicted to the hunt and to the passion that comes with the optimism of what is possible and I’m not cut out for later stage investing. I tried. I really tried. I gave it everything I had. FF was always supportive, however they are also stage agnostic and generalists and hoped I would be able to do all stages and I can not. I just can’t.

–Banister, on leaving Founders Fund in 2020 (Medium)

This moment could have been the termination of Banister’s limitless self belief—an end to childlike joy and wonder. It’s the great risk of adulthood: self-conception hits a wall and we retreat, feeling the world close in a little.

Instead, Banister saw it as an opportunity to re-focus on the part of her work that brought her the most intense joy: early-stage investing.

The real failure,” Banister told us, “would have been to try to make it work.”

Looking Up

For a fatherless daughter, Banister’s life has been shaped by a series of generous mentors. They have pushed her to learn, to reach higher, and to be more herself.

Her grandfather was the first such figure in her life, her husband Scott Banister another. Penn Jillette has been a friend for nearly twenty years.

Banister met Jillette before she was an angel, before she had even met Scott. She happened to go on a date with someone who was “obsessed” with Jillette. The relationship didn’t last, but he did pique her curiosity about the magician, who she remembered seeing on TV as a child.

When she finally had the chance to go to a Penn and Teller show, Banister happened to catch a card that flew around the room as part of the pair’s act. Afterwards, she took the card to the stage door to be signed.

Instead of signing it, Jillette took the card and put it in his jacket—and went right around signing autographs for the circle of fans.

When he made his way back around to her, he looked perplexed. “What are you still doing here?” he asked.

“You took my card,” she replied.

He looked down at the card. “Oh,” he said. “I thought you were giving me your number.”

She was not, but she was intrigued by the show so she tried sending an email to webmaster@pennandteller.com. Sure enough, Jilette remembered her (she had pink hair at this point, so she stood out from the crowd).

Banister and Jillette corresponded by email for more than two years before ever meeting in person. It was always platonic, Banister says, though he was amused to learn the story of her first discovering his work.

Jillette, she says, is an “amazing” person, whose guidance has helped her through some of the most challenging moments in her life. When she was deciding whether to leave IronPort to start Zivity, it was Penn’s encouragement that gave her the conviction to do so.

Another person she looks up to is Bill Murray. She speaks with authority about his films—Lost in Translation is her favorite and she doesn’t love the one about “some weird gopher thing.”

If there is a model for what it means to Banister to live a good life, Murray comes closest.

Like her, he is an iconoclast. He is known to crash parties and weddings. In 2006, he went to a college party and started washing dishes.

Banister finds beauty in the way he lives his life—but also sadness.

He doesn’t love himself enough...I think he does these things because it’s the only way he can be around normal people—you’re not going to stop Bill Murray from washing your dishes in order to take a selfie with him. It’s magic.

–Banister

She likes that he is always engaged in some kind of performance art.

Sometimes she does things “for entertainment” too. She’s wearing plaid, for instance, every day for the next three months. It’s a pattern her son picked out that she doesn’t even like all that much.

“It’s a forcing mechanism,” she explains, “when you go to the store and ask for things in plaid, what you find is that there just aren’t that many clothes. It stops me from buying too much.”

She gets up from the table and pulls out a plaid button down. She wrote “What is plaid?” across the back in glitter paint.

It’s a good question. She pulls out a red dress patterned with a kind of deconstructed crosshatching. Dan says it definitely is plaid. But KG isn’t so sure.

When Banister finally met Murray in person last year, she knew that they couldn’t just go for coffee or something formal; they had to do something natural. Murray loves to golf, so she decided to give it a shot with him.

A year later, she’s still working on her swing.

The idea of presence is something she thinks a lot about. In our five hour plus conversation, Banister didn’t check her phone a single time.

Everything he’s made is about the present. The past is yesterday, and the future is undetermined. This is how he lives his life.

–Banister

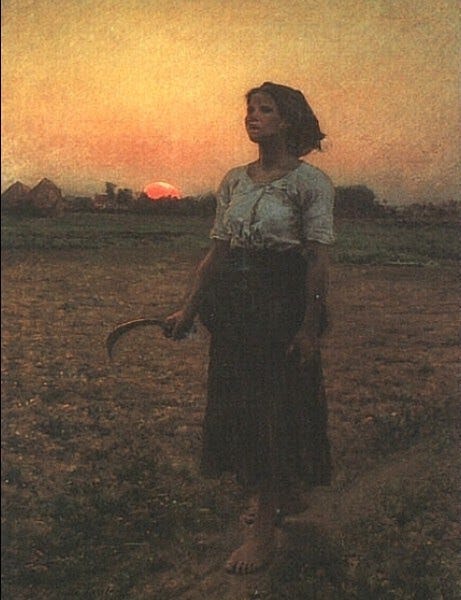

At a 2014 press conference, Murray explained how when he was facing suicidal thoughts early in his career, a Jules Breton painting—The Song of the Lark—saved his life.

[Breton thought] ‘Well, there’s a girl who doesn’t have a whole lot of prospects, but the sun’s coming up anyway and she’s got another chance at it.’ So I think that gave me some sort of feeling that I, too, am a person, and I get another chance every day the sun comes up.

–Bill Murray (Monuments Men Press Conference)

DS: You’ve done so much in your life—you’ve risen from poverty to build and invest in great companies, you have achieved extraordinary financial security, you have a family. What else do you want to accomplish?

Banister: “I want to make a piece of art. Something like [Song of the Lark]. I don’t know if it’s a building, a painting, a film, a sculpture, a piece of theater or what. Something that moves people.

Three years ago, Banister experienced her own near-death moment: a stroke. It was completely debilitating. She had two kids to take care of—one around six and the other in high school—and suddenly she required care herself.

She had to relearn how to walk, she had double vision for months, and she still takes blood thinners. But Banister—ever the optimist—says her stroke was “a gift.”

She looks up at us. The gray outside is fast turning to black.

“What matters will shock you,” she says. “Water, food, air, sun, and relationships.”

Thank you for reading Cyan: The enlightenment of an iconoclast. We hope you enjoyed it! And if you did, make sure to subscribe, send to a friend, or, if you’re on Twitter, give it a retweet (KG is @kevg1412).

We’d also like to thank Cyan for answering our many questions and taking the time to talk to us. You can read more about her remarkable life story on The Ugly Duckling or follow her on Twitter @cyantist.

We’ll be continuing our coverage of technologists, financiers, and operators in the coming weeks—starting with Garry Tan. Down the pipeline further are Carl Icahn, Mike Maples Sr., Josh Wolfe, Steve Jurvetson, Hans Tung, Ho Nam, and Martine Rothblatt. We’ll also be returning to our six-part series on founding venture capitalist Arthur Rock, and Part 2 on Bob Iger. If you know any of these people and feel moved to give us warm introductions, or even just personal stories, please reach out over email or Twitter.

Until next time,

Dan Scott and KG

Great read

AWESOME