Coming About with Bob Iger: Part One

Or how the House of Mouse set sail for a brighter future.

When Bob Iger wakes up, it’s still dark outside.

It will be another two hours before the late-winter sun grazes the peaks of the nearby San Gabriel Mountains.

Waking up early is essential, Iger says. It provides him a chance to think and read undisturbed before the demands of the day—and of his position as president and COO of the Walt Disney Company—pile up in his inbox.

On this particular Saturday morning though, it’s hard to imagine even Iger feeling all that much at peace.

It’s March 12, 2005.

The arduous, six-month-long succession process to replace Michael Eisner, Disney’s long-serving CEO, has come to an end. In a few hours, Disney’s board will call into a meeting in New York City to vote on whether or not to name Bob Iger as the company’s next CEO.

Following his standard 4:15 wakeup, he no doubt undertakes his daily routine; warming milk for wife Willow Bay’s coffee before heading to his workout room, turning on his music, his TV (on mute), turning off the lights, and stepping onto his VersaClimber—his choice workout/torture device.

The VersaClimber is also one of Lebron’s favorite exercise machines.

He works out seven days a week. But this morning, he must feel an emotional twinge with each stride of the VersaClimber.

30 years at a single company.

30 years of relentless devotion.

30 years of crescendoing responsibilities.

30 years of diplomacy with industry-leading difficult personalities.

30 years of navigating ferocious change to the media market with composure.

It’s all come down to today.

Bob Iger is Mr. Health—he practically glows of it, his 6’1 figure kept trim through middle age by road-biking (his favorite route is a 20-mile jaunt from Brentwood to Venice), by all that VersaClimbing, and by training for the Malibu Triathlon.

His face is classically handsome, softened by smile lines and a gentle bronze, no doubt thanks to occasional trips on his custom sailboat (though he wishes he could get out more).

I exercise for vanity and sanity.

–Iger (Coffee with the Greats podcast, 2020)

Iger speaks with the verbiage of someone who reads non-fiction for fun (he does). He has a particular fondness for the word “exhort”.

Though Eisner likes even his most senior executives to wear Mickey Mouse ties to work just like he does, Iger pretends to miss the memo. He’s not much for kitsch. In later years his PR chief, Zenia Mucha, would bend over backwards to keep him from being photographed in Mickey Mouse ears.

Over my dead body.

– Mucha’s reported reply to a reporter who asked to photograph Iger in mouse ears (Brooks Barnes, The New York Times)

Instead, Iger arrives at the office in a modest but modern style. Thoughtfully cut suits—and the occasional cardigan—give an impression of solidity; of someone deserving trust. His manner, guided by keen emotional intuition, is said to reinforce this sense.

He takes care to engage those he interacts with about their interests and accomplishments; meeting them on their terms. This takes thorough research, curiosity, and the ability to set aside ego—even if only for a moment. And it makes a difference. Disney employees remember brief interactions with him in glowing terms even years later.

If Disney were to make a film starring a male CEO, it’s hard to imagine finding anyone who looks, speaks, or acts more the part than Bob Iger.

But—surprisingly—from the beginning of the search, Bob Iger has not been the consensus choice for CEO. In fact, searing critics have emerged far and wide.

They have popped up among interested observers.

Critics have said that Iger lacked creative vision, faulting his role in overseeing the once-struggling ABC. Many viewed him as damaged goods because of his close ties to Eisner, whom shareholders rebuked last March with a 45% no-confidence vote.

– Richard Verrier and Claudia Eller (LA Times)

"There were many naysayers," recalls [an investor]. "People would call him 'mini-Eisner,' his yes man."

– Richard Siklos (CNN Money)

In the press.

He needs to heal Disney's diseased culture. He needs to harness the digital technologies that are transforming media. And he needs to lead a creative rebirth at the company...Little in his past inspires confidence that Iger can do it all….

He has not demonstrated that he can pick the right creative people and create an atmosphere where they will flourish….

No one disputes that Bob Iger is a good guy. But that doesn't necessarily make him a good CEO…

– Marc Gunther (CNN Money)

...bland, scripted CEO” whom no one would call “a big strategic thinker”...

– Devin Leonard (Bloomberg)

And—most troublingly for his prospects—on Disney’s board of directors.

At this point, here's how the contest stacks up: Three directors, including Eisner, support Iger. The other eight, to varying degrees, are open to the idea of an outsider infusing long- dysfunctional Disney with fresh blood.

– On the CEO selection process, Patricia Sellers (FORTUNE)

Roy E. Disney and Stanley P. Gold, who quit the Disney board in late 2003 and led the shareholder revolt against Eisner last year, accused the board Sunday of failing to find “a single external candidate interested in the job and thus handed Bob Iger the job by default.”

– Richard Verrier and Claudia Eller (LA Times)

Outraged by the process, Stanley Gold, a former Disney director who turned against Eisner, told FORTUNE, "Meg Whitman [a competitor for the position] created one of the great companies in the world out of thin air. What has Bob done?"

– Marc Gunther (CNN Money)

Even Iger’s strongest advocate, outgoing-CEO Michael Eisner, had previously expressed reservations about his candidacy.

Early on in Iger's tenure, Eisner wrote the board about Iger's prospects for becoming CEO someday: "He is not an enlighten [sic] or brilliantly creative man, but with a strong board, he absolutely could do the job."

– Patricia Sellers (FORTUNE)

...in a[n August 1999] discussion about succession, Michael said that I would never be his successor.

– Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Besides, Eisner’s support for Iger had been more of a liability than a lift.

The first, successful ten years of Eisner’s tenure had given way to a decade of cratering performance, particularly for Disney Animation Studios—the company’s flagship business.

As Eisner’s subordinate for that final decade, and his number two for the final five years, Iger’s prospects suffered by association. And his portfolio during the Eisner years included oversight of the ABC Group, which was being surpassed in the ratings.

Worse still, the board’s experience with Eisner—and their resulting skepticism of Iger—led them to conduct an overly rigorous, six-month search for a new CEO, pitting Iger against external candidates like eBay’s Meg Whitman.

The process brought the imperturbable Iger to the edge.

After fifteen interviews, often re-litigating the same questions, Iger felt humiliated. At one point, he experienced an anxiety attack while attending an L.A. Clippers game with his six-year-old son, Max.

But now decision day has finally arrived. Iger decides the best approach is to try to focus on something else.

I spent the day with my two boys, trying to distract myself. Max and I tossed a ball around, went to lunch, and spent an hour in his favorite neighborhood park. I told Willow that if bad news came, I was getting in my car and taking the cross-country drive that I’d long dreamed of taking. A solo trip across the United States seemed like heaven to me.

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Meanwhile, in a New York conference room, U.S. Senator George Mitchell of Maine, Disney’s chairman, helms a meeting of the board of directors. Most of the eleven members call in.

By the evening, the votes cast—unanimously by now—in favor of Iger, Mitchell, with Eisner by his side, calls Iger to congratulate him.

Once the call ended, Willow and I sat quietly for a moment, trying to savor it all. I had a mental list of the people I wanted to call right away, and I was fighting the urge to start dialing and instead trying to just be still, to breathe a bit, to let in both the elation and the relief.

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Now, with the exhausting selection process only just concluded, Iger would have to begin the real work.

He’d have to win over the many remaining doubters—who included Walt Disney’s nephew Roy E. Disney—then the largest holder of outstanding Disney shares besides Eisner. Roy Disney had been so unhappy with the Eisner status quo that he led a shareholder revolt resulting in a 45% vote of no confidence.

He did not take kindly to the board selecting Eisner’s number two.

[Roy E. Disney accused the board of not finding] “a single external candidate interested in the job and thus handed Bob Iger the job by default.”

– Richard Verrier and Claudia Eller (LA Times)

Another relationship that had been allowed to run aground under Eisner: Disney’s partnership with Steve Jobs, the majority owner and CEO of Pixar.

The once-fruitful co-production and distribution deal that yielded hits like Toy Story, A Bugs’ Life, and Monsters Inc. had devolved into nasty, ego-fueled sniping between Eisner and Jobs.

In his characteristically blunt fashion, Jobs called some of Disney's recent films "duds" and "embarrassing"....

Jobs...told stock analysts that Pixar consistently made smash hits such as "Finding Nemo." Meanwhile, Disney turned out "Treasure Planet" and "Brother Bear," and "both bombed at the box office," he said.

– Benny Evangelista (SFGate)

Yesterday we saw for the second time the new Pixar movie, Finding Nemo, that comes out next May. This will be a reality check for those guys. It's okay, but nowhere near as good as their previous films. Of course they think that it's great."

– Eisner in memo to staff, leaked to press. (USC Third Space)

With Disney Animation flailing, and the soon-expiring Pixar deal as the only remaining bright spot, patching things up with Jobs would be mission critical for Iger.

It would also be an uphill battle. After telling his family about his new job on the morning of Sunday, March 13, Iger called Jobs.

[Jobs’s] response [to my selection as CEO] was basically “Okay, well, that’s cool for you.” I told him that I’d love to come see him and try to convince him that we could work together, that things could be different. He was typical Steve. “How long have you worked for Michael [Eisner]?”

“Ten years.”

“Huh,” he said. “Well, I don’t see how things will be any different, but, sure, when the dust settles, be in touch.”

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

But even if Iger didn’t perceive it in Jobs’ tone, Jobs was touched by his outreach.

When Iger got up [the morning after being named CEO], he called his daughters and then Steve Jobs….He said, very simply and clearly, that he valued Pixar and wanted to make a deal. Jobs was thrilled.

– Walter Isaacson (Steve Jobs)

So touched, in fact, that Iger’s simple outreach to Jobs would lead to a partnership that would in turn be the first step of an epic quest to remake the Disney empire. It was also the start of a deep friendship. Jobs would later tell his wife Laurene, when she asked if Iger could be trusted, “I love that guy.”

This exchange would set in motion a series of acquisitions—commencing with Pixar in 2006, followed by Marvel in 2009, Lucasfilm in 2012, BAMTech in 2017, and certain 21st Century Fox assets in 2019. These savvy deals would transform Disney and cement Iger’s reputation as one of America’s all-time greatest public CEOs.

Now, when he steps onto his VersaClimber at the break of dawn, Iger can look back on a nearly 15-year tenure during which he accomplished what many considered impossible.

He quadrupled the company’s market cap.

He released 27 of the 50 highest-grossing films of all time. And through the Fox acquisition, Disney now owns 30.

He kept the Disney brand relevant in a rapidly changing media ecosystem—and kept the company competitive with behemoth competitors AT&T and Comcast (the latter of whom tried to acquire Disney for $55 billion the year before Iger ascended to the top role. DIS market cap is $319 billion as of this publication.).

He turned around Disney’s core business—its animation studio. Hits like Frozen, Frozen II, Zootopia, and Moana restored the Disney brand to its hallowed position of cultural prominence and provided IP-as-ammunition for the rest of its divisions (theme parks, resorts, merchandising, live theater, etc.) to flourish.

While Iger is celebrated for his accomplishments—particularly after the 2019 publication of his bestselling memoir The Ride of a Lifetime and his retirement from the CEO role in February 2021—in the final analysis, we believe that Iger is still under-appreciated as a public company operator.

His results would have been extraordinary for a CEO handed any company in good health.

But the under-covered reality is that few at the time understood the extent to which Disney’s future was in peril, not even Disney’s board.

After Iger described the bleak state of affairs in his first board meeting as CEO, the room “got quiet.”

...we projected onto a screen the list of films put out by Disney Animation over the last decade: The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Hercules, Mulan, Tarzan, Fantasia 2000, Dinosaur, The Emperor’s New Groove, Atlantis, Lilo and Stitch, Treasure Planet, Brother Bear, and Home on the Range. Some were mild commercial successes; several were catastrophes...Over that stretch, [Disney] Animation had lost nearly $400 million….[The board] had no idea the numbers were this bad.

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

He is a turnaround CEO and should be considered in the same breath as Steve Jobs, who returned in 1997 to revitalize an ailing Apple Computer; Lee Iaccocca, who led a listing Chrysler to its 1980s renaissance; Sergio Marchionne who revitalized a laughingstock of a company in Fiat that had gone through 4 CEOs in 3 years; Lisa Su, the CEO of AMD; and Satya Nadella of Microsoft.

Ironically enough, Iger himself took over from another turnaround CEO. Eisner’s tenure began in 1984, when the company’s prospects looked exceedingly bleak. Though he successfully turned things around, Eisner’s legacy was ultimately complicated by his inability to sustain this early performance and his reticence to turn over the company to someone who could.

Regardless, Iger enjoys rarefied company. CEOs who have led sustained, successful turnaround are few and far between and their CEO-ships offer myriad management lessons. Large companies tend towards stasis—lumbering tankers, liable to keel over if their course is too quickly changed.

This problem is especially acute in the creative industry, whose output is highly reliant on collaborations amongst creative talent working on long project lead times (at Disney, animated films can take up to 7 years from initial development through release). The controls to turn the ship around—even when the will exists—are often too cumbersome or ill-defined.

That makes Iger’s deft piloting all the more impressive.

As a self-taught sailor, Iger knows the in-and-outs of changing tack. Coming about, as it’s called, is done as a matter of course. The maneuver must be executed swiftly, calmly, and strategically to avoid losing momentum.

His turnaround of the Disney ship—executed swiftly, calmly, and strategically—was second to none.

Iger’s path to becoming a once-in-a-generation leader is a testament to the importance of hard work and discipline. It’s also a reminder of the necessity of cultivating emotional intelligence and treating others with respect.

Principally, though, Iger’s is a story about learning and implementation.

He took learnings from his mentors/fairy godparents—Roone Arledge, the head of ABC Sports; Tom Murphy and Dan Burke, the leaders of Capital Cities/ABC; and Michael Eisner, Iger’s boss and predecessor—and applied their lessons in unexpectedly dazzling combination.

From Arledge, Iger learned to achieve perfection in visual storytelling; from Murphy and Burke, how to manage people; and from Eisner, how to evaluate other aspects of Disney’s creative output and how not to do acquisitions or manage creative personalities (or an animation studio for that matter).

He would re-mix and crystallize learnings from these teachers into a series of three strategic priorities in his campaign for the job of CEO:

1. Re-orienting the company around high-quality branded content,

2. Embracing technology, and

3. Expanding Disney’s international reach.

As CEO, these priorities guided him to a series of five enormous, climactic acquisitions—Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, BAMTech, and parts of 21st Century Fox—and two company-defining internal projects: Shanghai Disneyland (opened in 2016) and the Disney+ streaming service (launched 2019).

Collectively, his efforts—supported by his senior team, who included Kevin Murphy, Tom Staggs, and Zenia Mucha—have put Disney on a course to live happily ever after.

We should note: this is not a biography. Iger has that covered, with his book The Ride of a Lifetime. It’s well worth a read.

Instead of covering each detail of his life, this piece sets out to understand how a diplomatic company man from Long Island climbed the corporate ladder and shook up one of America’s two longest-running iconic brands (the other: Coke) to make it competitive for the new millennium.

ORIGINS: The boy from New York City

Iger was born on February 10, 1951 in Brooklyn, NY.

When he was five, his parents moved him and his younger sister Carolyn to Oceanside, on Long Island; the Southern part of Hempstead, NY. The hamlet boasted good schools and a rapidly growing population fueled by the postwar building boom.

His childhood was shaped by the kinds of things a Jewish kid growing up in post-war Long Island might be obsessed with.

He watched the Mickey Mouse Club and Disney’s Davy Crockett.

He attended his first baseball game in 1955, at Ebbets Field in Flatbush, where he watched the Brooklyn Dodgers play. It was a legendary year for the Dodgers, who would go on to win the World Series led by Sandy Koufax (whose rookie baseball card and signed ball he has) and Don Newcombe.

To this day, his memory of this era’s New York baseball history is encyclopedic.

The Brooklyn Dodgers’ 1957 move to Los Angeles would precede Iger’s by several decades. After their departure, his allegiance transferred to the Yankees (“My dad said we will never root for [the Dodgers] again”) then led by one of his heroes—Mickey Mantle.

Iger was so infatuated with Mantle, that he decided to name one of his sons ‘Mickey’, he says, but by the time he had his first boy, he was working for Disney.

I thought if I named my son Mickey, he would be forever scarred.

– Iger, Coffee with The Greats, Miles Fisher

His first basketball game saw the Knicks (whose games he still buys tickets to) meet the Celtics at the old Madison Square Garden.

He has been a “diehard” Greenbay Packers fan since 1960.

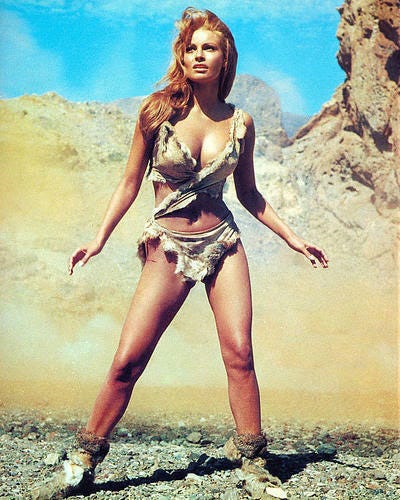

He would one day become the chief of America’s most family friendly company, but he spent the nights of his youth sleeping beneath a poster of Raquel Welch.

His parents later covered the room’s walls (and the erstwhile poster) with a homemade wallpaper pieced together from New Yorker covers.

Parents with New Yorker covers to spare might be expected to be cerebral—and Iger’s were.

His father, Arthur Iger, a World War II Navy veteran and jazz trumpeter who tried, often unsuccessfully, to hold down jobs in advertising and publishing, was the president of the Oceanside school board. Iger’s mother, Mimi Iger, was a junior high school librarian. They purchased the family’s split-level home for around $10,000 with a zero-interest mortgage from the GI Bill.

The family lived on a street in Oceanside, Iger says, on which just about every father had been a veteran. But Iger’s father was not like those of his friends in one important respect: Arthur Iger struggled with bipolar disorder, or what was then called manic depression.

We never knew which Dad was coming home at night, and I can distinctly recall sitting in my room on the second floor of our house, knowing by the sound of the way he opened and shut the door and walked up the steps whether it was happy or sad Dad.

– Iger, (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Iger doesn’t bemoan this experience, though. He says he had a good childhood. He is grateful, he says, for the fortitude that his father’s illness taught him.

It’s also clear that his early experiences with his father shaped the way that Iger relates to other people. Children of bipolar parents often learn to feel responsible for managing their parent’s moods. The way Iger describes clocking his father’s emotional state, for example, is also a crucial skill for engaging people of all stripes—whether they be counterparts in a negotiation, subordinates in a meeting, or an interviewer.

He is said to make people he is talking to feel singularly important.

I had a boss [Dan Burke] that treated me that way—every time I went into his office, I felt like I was the most important person in the company. And I realized at some point that every person in the company felt like they were the most important person in the company when they met him, so it wasn’t just me. But it was a characteristic that I tried to emulate, because it was so empowering to people.

– Iger (interviewed by Oprah at 92nd St Y, 2019)

Iger is also famous for his even-keeled, consistent calm in the face of crises. This could also be attributed to a reaction against his father’s condition.

[Iger’s] big break came at the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics, where he oversaw the scheduling. When snow melted in the warm weather, causing a crisis for the network and a high degree of anxiety for everyone, Bob’s coolness under pressure [earned him recognition]...Anyone who could stop snow from melting before an Olympics broadcast had a big future at the network!

–Michael Eisner (Work in Progress)

Despite the hardships, Iger takes pains to paint a positive portrayal of his father. At one point in The Ride of a Lifetime he tells the story of his father fighting (in the 1960s) to protect the job of a teacher who was about to be fired for being gay.

Iger posts an annual Veterans’ Day remembrance of his father.

Iger’s great uncle, Jerry Iger, was a cartoonist—famous for co-creating, with a man named Will Eisner (no relation to Michael) “Sheena: Queen of the Jungle,” a wildly popular comic book series which featured Sheena, a scantily clad female protagonist raised amongst jungle creatures.

Iger—who, through Marvel, would go on to control the plurality of the U.S. comic book market share—says his great uncle Jerry, whom he describes as a “rogue” often clad in zoot suits, left a lasting impression.

Early on, I went to his apartment in New York—he was very urbane—and I opened some drawers in a studio in his apartment and I think it was the first equivalent of pornography that I had ever seen.

– Iger (Coffee with the Greats, 2020)

Perhaps just as formative, his great uncle’s creations also provided Iger exposure to the value of IP. Sheena (incidentally, the first female-titled comic book series) earned a spin-off from her original comic series, prose stories in another comic, two syndicated television series, and a 1984 Columbia Pictures film.

At the age of 15, Iger determined that his dream in life was to be the next Walter Cronkite. It’s the kind of quiet, earth-shattering ambition Iger would later become known for.

Walter Cronkite was at the peak of his power and popularity as an anchor, and I set my sights on being Walter Cronkite. [Laughing] Because why not have lofty goals?

–Iger (interviewed by Variety, 2015)

In school, meanwhile, Iger’s parents expected him to exercise discipline and work hard, though it’s difficult to tell how much of this was his parents’ exhortation versus natural inclination. In high school, Iger went to infinity and beyond (we apologize) with a list of high school extracurriculars that included gymnastics, the student mock court club, and a role in school plays, including The Crucible. He was also a member of the student radio broadcast club—a new club at Oceanside High, which was then on the verge of becoming an FM radio station.

His senior year, his classmates crowned him the “most enthusiastic” member of his graduating class.

He also had to work to earn money alongside school from a young age. His work experiences included one formative summer spent scraping dried gum off the bottom of desks at school. His parents were closer to poverty than they ever let on, he would later write.

His senior year, Iger chose to attend Ithaca College over Cornell. Though he hasn’t addressed why he did it, it’s possible that its well-regarded Television-Radio degree program appealed to him as the path to broadcasting glory.

Iger would maintain his affiliation with Ithaca College for many years. He would be its its 1993 commencement speaker and join Ithaca’s board of trustees in the late 1990s.

We must always entertain with a conscience, and inform according to the highest journaistic and ethical standards.

–Iger (Ithaca College Commencement Speech, 1993)

I’m not necessarily an appropriate join the discuss the real world. After all, I work in television.

–Iger (Ithaca College Commencement Speech, 1993)

Once in a while every one of us gets lucky.

–Iger (Ithaca College Commencement Speech, 1993)

I’ve had some of the best winners and I’ve had some of the biggest losers the networks have ever seen.

–Iger (Ithaca College Commencement Speech, 1993)

As an undergrad, Iger worked hard to pay his way through college. He spent his weekends as a freshman and sophomore making pizza at a Pizza Hut franchise. His customers likely would have many fellow Ithaca students enjoying the weekend without him.

By his senior year, his involvement in extracurriculars was nothing to look askance at either. In preparation for his career as the next Cronkite, he was the program director and sports director of WICB-TV, the Ithaca student television station.

He hosted a segment called campus PROBE.

*Note: Start video at 10:15 if it doesn’t automatically.

Besides his broadcasting obligations, he was also a student advisor, a member of student congress—a political interest presaging his almost-run for president in 2020—a lab instructor, a member of the personnel committee, and a participant in intramural sports.

Of his college years, Iger says that “something clicked” academically. He was committed, he says, to “working hard and learn[ing] as much as [he] could,” in order to not end up feeling like a failure, as his father had.

Iger graduated in 1973 with a degree in broadcast journalism, and as a member of “Oracle”, Ithaca’s honor society.

Up the ladder/Roone Arledge

Iger’s first job out of college was at a local cable television station in Ithaca, where he was hired as a weatherman. More often than not, his job entailed bearing bad meteorological news to Ithaca residents, socked in by low clouds and snow much of the year.

The experience, he says, offered training in an essential leadership skill: breaking bad news.

Reporting on snowstorms ad infinitum, Iger began to come to terms with the fact that he did not possess the requisite talent to pursue a career as a television news anchor, no matter how much—or for how long—he had wanted to.

I was working as a weatherman and a feature reporter. I could tell pretty quickly that, while I might have had the ambition, I didn’t have the confidence on the air. I just didn’t think I was good enough or quick enough or confident enough.

–Iger (Variety, 2015)

It was time to pivot.

Iger returned south to the Big Apple where he found his way into a production job at the bottom of the ladder at ABC Television.

The position arose through happenstance: Iger’s uncle had an especially talkative hospital roommate following an eye procedure, who just so happened to lead a small department within ABC. Iger’s uncle inquired on his behalf, and before he knew it, Iger was the proud owner of a $150-a-week job as a studio supervisor at ABC.

The position was a differently named production assistant role—Iger bore responsibility for coordinating with various members of the crew, making sure they had access to the studio, ensuring union rules are followed, executing logistical tasks, and running various errands for the shows’ producers.

Television jobs—especially at the bottom rung—are demanding. They require an ability to think and respond to problems rapidly, considerable stamina, and calm under stress. It was here Iger began to develop his legendary professional work ethic.

Maybe most important, I learned to tolerate the demanding hours and the extreme workload of television production, and that work ethic has stayed with me ever since.

–Iger on this period (The Ride of a Lifetime)

The portfolio of TV shows in Iger’s studio included long-running soaps like All My Children and One Life to Live, a game show called The $10,000 Pyramid, and ABC’s flagship The ABC Evening News with Harry Reasoner, among others.

Iger enjoyed the work, especially when it brought him in contact with interesting people, like Frank Sinatra. While still a studio supervisor at ABC television, Iger was tapped to be an assistant on the set of a 1974 televised concert featuring Ol’ Blue Eyes at Madison Square Garden. It was called The Main Event. Sinatra left Iger with a $100 dollar bill and a gold lighter (given to every member of the crew) for the trouble of picking up mouthwash for him.

The event was also the first time Iger saw Roone Arledge in action. He got a memorable taste of his demands of television perfection. The night before the concert aired, Arledge said that the production wouldn’t do and would have to be completely reimagined.

Iger would later work full time for Arledge (and then vice versa, following Iger’s head-spinningly rapid promotions), but for now, he remembers relishing the opportunity to see the legendary creative mind at work on the details—up close and personal.

The concert gave Iger a taste of the first of three vital lessons he would learn from Arledge: the importance of pursuing perfection no matter the cost.

It’s about creating an environment in which you refuse to accept mediocrity.

–Iger on learning from Arledge (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Following a harrowing run-in with a corrupt department head within ABC, who told him he was “unpromotable”, Iger made the move to ABC Sports, Arledge’s celebrated, supremely profitable division. At Sports, he would begin his swift ascent of ABC’s corporate ladder in earnest.

Iger’s tenure at Sports began with more menial work—including delivering physical reels of tapes to editors and producers—and ended with trips on the Concorde; jetting off to glamorous, international climes to negotiate coverage deals and produce sport events for ABC’s Wide World of Sports.

His rise was dizzying; at 23, he was running errands and by 34, he had assumed the role of vice president at ABC Sports, reporting directly to Arledge.

At Sports, thanks to Arledge’s demanding and inspiring leadership, Iger would learn the scrappy business of television. For example, as the member of the team responsible for negotiating coverage rights to a table tennis championship in Pyongyang, Iger would develop experience negotiating with hostile foreign governments. This would serve him later when, at Disney, he spearheaded the 17-year negotiation and construction process for the Shanghai Disneyland theme park, which opened in 2016.

Iger was responsible for overcoming international sanctions in order to secure broadcast rights for the 1979 World Table Tennis Championship in Pyongyang, North Korea.

Through his international travel at Sports, he would also gain a sense that the world was smaller than geopolitical differences would make it out to be.

I also saw the ways in which [people living behind the Iron Curtain’s] dreams were no different from the dreams of the average person in America. If politicians had an urge to divide the world or generate an us-versus-them, good-versus-bad mentality, I was exposed to a reality much more nuanced than that.

– Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

It’s no accident that Iger would go on to lead, under Eisner, a reorganization of the international parts of Disney’s organization, and that as CEO, he would make one of his three priorities the international growth of the Disney brand.

This core insight from his days at ABC Sports—that while people may live in very different places (substitute Chinese citizens for people living behind the Iron Curtain), they are all moved by stories—would animate his push to make the Disney brand available and relevant to international audiences everywhere.

It was at sports, under the tutelage (and sometimes demoralizing supervision) of Arledge, that Iger came to understand storytelling as well.

Arledge had pioneered a new method of covering sports, which was most famously exemplified by his approach to covering the Olympics—which is now standard.

Arledge asked: how do we get TV viewers to care?

He really thought that the secret to engaging sports fans was telling great stories...one of the ways that he did that was he scoured the world...for interesting athletes, and made sure you cared about the athletes before you watched them in competition.

So if we were preparing for an Olympics in Montreal, Canada in 1976, he made sure that you knew who Nadia Comăneci was even though she was an obscure Romanian gymnast so that when she ends up competing and gets a 10 in the Olympics, you care about her not just for the performance, but you know who she is as a person.

– Iger (Coffee with the Greats)

By broadcasting competitors’ backstories, Arledge believed, even the most esoteric sports could become compelling.

It would also serve as a valuable lesson about the emotional power of storytelling—the core of Disney’s business.

Disney fans buy their children Elsa dolls and take them to see the new Frozen attraction because emotional context has been clearly established. This is the power of Disney’s IP, and it’s why Disney Animation—the company’s primary IP engine—is so crucial to the company’s success. It is responsible for establishing those emotional connections in the first place; the equivalent of the ABC Sports journalist reporting the personal backstory of an athlete so that the audience identifies with the outcome of their event.

Later, when he was installed as the head of ABC Entertainment, Iger would think back to learnings from Arledge about how to properly structure, pace, and add clarity to stories.

Finally, Arledge taught Iger to embrace technology. Arledge fiercely believed in the power of technology to make storytelling better—providing tools to make it more effective and more entertaining.

Arledge introduced, for example, slow-motion replays and live satellite coverage to his events to pump up audience understanding and engagement.

Roone taught me the dictum that has guided me in every job I’ve held since: Innovate or die, and there’s no innovation if you operate out of fear of the new or untested.

– Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Leading the industry on technology would be a career-long maxim for Iger, particularly on the content delivery side. This focus would make its way into Iger’s three core strategic priorities when he took over Disney in 2005.

The minnow swallows the whale/Tom Murphy and Dan Burke

The year is 1984 and the first of Iger’s career-defining acquisitions arrives on his doorstep.

Capital Cities Communications, a substantially smaller company, acquires ABC.

Cap Cities, run by Tom Murphy and Dan Burke, had previously owned only local television stations. But with financing from Warren Buffett, the pair were able to make the leap of an acquisition.

Unlike his later deals, Iger did not orchestrate the takeover. In fact, him and his ABC colleagues were “blindsided” by the deal.

Iger and the television elite at ABC were suspicious of their new owners. They looked down on Murphy and Burke as penny-pinching small-timers, given their reputation for running their local news stations on a shoestring budget.

But Iger would find himself surprised.

Like Arledge before them, Murphy and Burke would teach Iger invaluable lessons. Through their example and their concerted efforts to professionally empower him, Iger would learn fundamentals of business management that would shape the rest of his career.

Iger could hardly have wanted for more able teachers.

Tom Murphy and [his long-time business partner] Dan Burke were probably the greatest two-person combination in management that the world has ever seen or maybe ever will see.

– Warren Buffett (The Outsiders)

Whereas media companies were often cutthroat places lacking focus on team cohesion, Murphy and Burke brought this to ABC in spades.

They had the team do team-building exercises at a retreat in Phoenix—to sneers. Over time, their unique vision of decentralized management earned converts and inspired devotion. Murphy and Burke’s subordinates felt trusted and trusted their bosses in return. Many even worked for Murphy and Burke despite receiving lower pay than they might have elsewhere.

A turning point in Iger’s relationship with Burke and Murphy came in 1988, when Iger helped to plan ABC’s coverage of the Calgary Winter Olympics. After a major weather disaster (temperatures rose to the 60s), and many event cancellations, Iger helped stitch together ABC’s coverage—which earned historic ratings.

Watching from their seats in the back of the control room, Murphy and Burke were impressed.

They noticed his calm under pressure—a vital trait in television production. Murphy and Burke named Iger—just thirty-seven—the new executive vice president at ABC Television.

Here, Iger enjoyed the benefit of a fundamental Murphy-Burke commitment: to value talent over experience. This principle would shape Iger’s personnel decisions throughout his career.

I’d primarily worked in sports, and now I would be running daytime and late-night and Saturday morning television, as well as managing business affairs for the entire network. I knew precisely nothing about how any of that was done, but Tom and Dan seemed confident I could learn on the job.

– Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

But even this wasn’t to be the end of Iger’s improbable climb under Burke and Murphy.

A short while after his first promotion, the pair again tapped Iger: this time to head ABC Entertainment, the division of the company responsible for producing and distributing scripted entertainment.

Even more so than in his fast promotion to executive vice president, Iger felt out of his depth running Entertainment. He would be responsible for developing television shows; reading scripts, dealing with talent, and programming primetime scripted entertainment, a set of skills he simply did not possess. He would also need to build credibility with subordinates and the broader Hollywood creative community.

While Iger learned a great deal about management generally from Murphy and Burke, at Entertainment—thanks to their trust in him—he would learn how to manage creative talent specifically.

As a result of his need to quickly ascend a steep learning curve, he learned another important principle about managing large, complex companies: don’t fake knowledge in order to appear impressive.

You have to ask the questions you need to ask, admit without apology what you don’t understand, and do the work to learn what you need to learn as quickly as you can. There’s nothing less confidence-inspiring than a person faking a knowledge they don’t possess.

– Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Creative managers who are out of their depth, he says, often focus on the small details to demonstrate to creatives that they have taste and mask their inability to deliver big-picture feedback. Really, Iger says, this habit betrays a lack of knowledge.

Murphy and Burke taught Iger another management trait he would extoll in later years: the importance of allowing people to fail in service of interesting and valuable risks.

The Murphy-Burke spirit of risk-taking even infected Iger—the alabaster model of discipline and restraint.

He took several big risks during his time leading ABC Entertainment—with mixed results. At Entertainment, he greenlit Twin Peaks, a daringly dark thriller from David Lynch; NYPD Blue, a standards-pushing procedural; and Cop Rock, a cop drama with music by Randy Newman. Its Wikipedia page calls it “one of the biggest television failures of the 1990s.

Note: If we’re honest, it kind of slaps. Wikipedia should give it another look…

At Cop Rock’s wrap party Iger told the cast and crew, ”We tried something big and it didn’t work. I’d much rather take big risks and sometimes fail than not take risks at all.”

Iger credits Burke and Murphy with empowering his continued risk-taking through their remarkable faith in him.

It was a virtuous circle, though; despite some missteps, Iger also delivered major results. The more he delivered, he says, the more latitude he was given. With hits like Home Improvement, America’s Funniest Home Videos (a home-video compilation show that was remarkably prescient of TikTok), NYPD Blue, and Grace Under Fire, Iger’s prime time slate displaced NBC at the top of the ratings in the “key demo”, adults aged 18-49. NBC had held the top spot for more than a year—a feat in the highly competitive world of primetime television.

When NBC’s president, Brandon Tartikoff, called Iger to congratulate him, Iger, ever the baseball fan, ever the diplomat, jokingly demurred.

“I feel a little sad about it,” I told him. “It’s like Joe DiMaggio’s streak coming to an end.”

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Iger also green-lit a new television show by George Lucas, chronicling a young Indiana Jones’ adventures: The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. The decision to do so, though not generative of commercial success (the series lasted only two seasons), planted the seeds of a trusting relationship between Lucas and Iger that would be reaped two decades later with the acquisition of Lucasfilm.

After his five year run at Entertainment, the winds of upward mobility once again filled Iger’s sails. He was tapped for another promotion—this time to be president of ABC in New York. Now, at age 42, Iger’s mentor Roone Arledge would be reporting to him.

Then, in 1994—another rapid promotion just one year and nine months later. Dan Burke retired, and Tom Murphy asked Iger to take Burke’s place as the president and COO of Cap Cities/ABC, the number two job at ABC Television’s parent company.

It was a staggering rise.

His success at every stage, he says, was the result of the faith Murphy and Burke placed in him—not just through the fact of this promotions, but in their words of encouragement at each step along the way.

Welcome to the Magic Kingdom/Michael Eisner

At the point when Disney’s course crossed Iger’s, Michael Eisner had been CEO of Disney for just over a decade.

Eisner—another towering New Yorker, at 6’3 (but from Park Avenue; not Brooklyn) and also the son of a WWII veteran—would be the final formative mentor figure in Iger’s rise to the top of Disney’s parapet. (Their roots, interestingly enough, are not where the commonalities end: Eisner also started his career as an entry level employee at ABC in New York and swiftly rose through the network’s ranks to become senior vice president only a decade later. Iger was still a low-level employee at this point, and the two’s paths didn’t cross.)

Along with Frank Wells, Eisner’s COO and number two, and Jeffrey Katzenberg (who would later leave Disney to found Dreamworks after being passed over to replace Wells) as the head of Disney Studios, Eisner had engineered the company’s return to prominence. Hits like The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King inaugurated a renaissance for Disney Animation and returned the company to financial success.

Eisner and Wells were a powerful duo—the Timon and Pumba of the entertainment world—with Eisner plotting and perfecting Disney’s creative output and Wells making it all happen operationally.

Wells would tragically die in a 1994 helicopter accident. He would be unable to see through the new plan to “reinvent and reenergize Disney” that he and Eisner had concocted—replete with new businesses and executive changes in order.

One enormous change the pair had been exploring: the largest acquisition in Disney’s history, and one of the largest in U.S. history. In 1995, a decade after ABC was swallowed by Cap Cities, Disney announced, to great fanfare, that it would be acquiring Cap Cities/ABC. The deal effectively doubled the size of The Walt Disney Company and locked Iger into a five-year contract working under Michael Eisner, though not necessarily reporting directly to him—a matter of some contention.

With the merger, Iger clocked the first of many lessons from Eisner: understanding the value of big, bold acquisitions.

Michael never got much credit for having the guts it took to make that deal, but it was an enormous risk, and it paid off for years to come. The acquisition gave Disney the scale to remain independent when other entertainment companies were coming to the painful realization that they were too small to compete in a changing world.

–Iger (Ride of a Lifetime)

In fact, Iger recognized the value of the deal early on. According to Eisner, Iger told him so in one of their earliest conversations: “I want you to know that I totally support [the deal],” Eisner reports Iger telling him. “I think that it makes sense from a business standpoint.”

Before the acquisition, Iger was widely assumed to be next in line for Murphy’s position as CEO of ABC/Cap Cities. His new role under Eisner would feel like a demotion. Despite this, Iger didn’t make a stink. In fact, he remained ever optimistic.

While Bob had more reason than anyone to feel disappointed when we bought ABC, he never complained. Instead, he jumped into his expanded role.

–Eisner (Work in Progress)

Iger would be in charge of integrating ABC/Cap Cities into the Disney fold—his second exposure to a major acquisition, but the first he would have a major hand in executing. He would lead the merger with all the outward grace of an Olympic figure skater on ABC.

Like Murphy and Burke before him, Eisner appreciated Iger’s calm through challenging and complex circumstances.

During a difficult transition, Bob brought to his job a sense of unflappability that made people around him comfortable and secure.

–Eisner (Work in Progress)

Eisner’s telling, though, didn’t recognize just how much discipline this unflappable appearance took to maintain. The transition was bruising—both for Iger personally and for Disney’s newest cast members: the ABC/Cap Cities team.

Very early in his tenure, Iger was layered by Michael Ovitz—the CAA co-founder-turned-media executive. Despite Eisner and Ovitz’s strong relationship, the hire did not work out. After a mere fifteen months as Iger’s boss, Ovitz was out with a $140 million golden parachute (a payout which was litigated for a decade afterwards as a possible breach of fiduciary responsibility. The case is still taught in law schools.) Eisner admitted to Iger that the decision to hire Ovitz was “a disaster.”

All this drama for a position that Iger felt ready to assume.

Simultaneously, Disney’s culture came crashing down on the newly integrated ABC/Cap Cities team. Where ABC had been decentralized, decisions big and small at Disney were routed through the company’s all-powerful Strategic Planning group—whom Iger refers to as a group of “aggressive, well-educated executives” with MBAs from Harvard and Stanford.

Iger refers to his early interactions with this group as “run-ins”. The ethos of the Strat Planning group was anathema to Iger (who would later note his pride in his outperformance of people from elite backgrounds). When it was finally his turn to run Disney, he would disempower the group in service of building a more decentralized culture—in accordance with the principles of Burke and Murphy.

Despite the turbulence, Iger committed himself to observing and learning from all that was happening around him.

And learn he did.

He learned from the disintegration of Eisner’s relationship with Ovitz—and later, Jobs—how not to manage relationships.

They should both have known that [the partnership] couldn’t work, but they willfully avoided asking the hard questions because each was somewhat blinded by his own needs. It’s a hard thing to do...but those instances in which you find yourself hoping that something will work without being able to convincingly explain to yourself how it will work—that’s when a little bell should go off…

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

He learned from Eisner’s hot-and-cold treatment of him how not to treat up-and-coming subordinates.

We all want to believe we’re irreplaceable. The trick is to be self-aware enough that you don’t cling to the notion that you are the only person who can do this job.

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

And he learned—crucially for his future acquisitions—how not to manage a company through such a transition.

Some of this learning came through his own missteps as the architect the merger and head of the ABC Group.

Our fortunes at ABC went downhill….In a matter of a couple of years, we’d slipped from being the most-watched network on television to the last of the “big three,” and we were barely holding on to that.

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

But Iger stuck it out, and by December of 1999, was offered the position of president and COO of Disney and given a seat on the company’s board.

Eisner offered a few important positive learnings as well. His strength had always been on the creative side of the business, particularly in managing the company’s theme parks. During this period, despite not being, as Iger puts it “a natural mentor” he took Iger with him on his reviews of Disney’s parks, illustrating to him the minutiae of a customer’s experience—much as Arledge had helped craft his thinking about television events.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that he taught me how to see in a way I hadn’t been able to before….I learned what the creative and design essence of our parks should be.

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

Eisner’s keen eye was not enough to keep the company out of trouble though.

After the turn of the millennium, Animation turned out a series of flops including The Emperor’s New Groove, Atlantis: The Last Empire, and Brother Bear.

Disney’s relationship with Pixar—whose films it distributed and were the only bright spot in the company’s animated offerings—was on the outs.

ABC’s ratings continued to slide.

Even attendance at Eisner’s beloved parks was on the decline.

And his overriding pessimism about this woeful state of affairs was depressing morale and making the company’s performance all the worse.

Michael had plenty of valid reasons to be pessimistic, but as a leader you can’t communicate that pessimism to the people around you. It’s ruinous to morale. It saps energy and inspiration. Decisions get made from a protective, defensive posture.

–Iger (The Ride of a Lifetime)

This was to be Iger’s inheritance.

This has been the first part in our two part series: Coming About with Bob Iger. We hope you enjoyed it! And if you did, make sure to subscribe, send to a friend, or, if you’re on Twitter, give it a retweet.

Next time: Bob Iger is named Disney CEO. Stay tuned to find out how he dealt with the hot mess on his hands, how he negotiated his way into a series of legendary acquisitions with owners and operators who weren’t initially looking to sell their companies, and how he opened a massive new Disney park in Shanghai.

We’ll explore how Iger used each acquisition to bring Disney one step closer to his strategic priorities—and how this set the company up for success.

We’ll be continuing our coverage of technologists, financiers, and operators in the coming weeks—starting with Cyan Banister. Down the pipeline further are Mike Maples Sr., Josh Wolfe, Steve Jurvetson, Garry Tan, and Martine Rothblatt. We’ll also be returning to our six-part series on founding venture capitalist Arthur Rock, and of course, Part 2 on Bob Iger. If you know any of these people and feel moved to give us warm introductions, or even just personal stories, please reach out over email or Twitter.

Until next time,

Dan Scott and KG